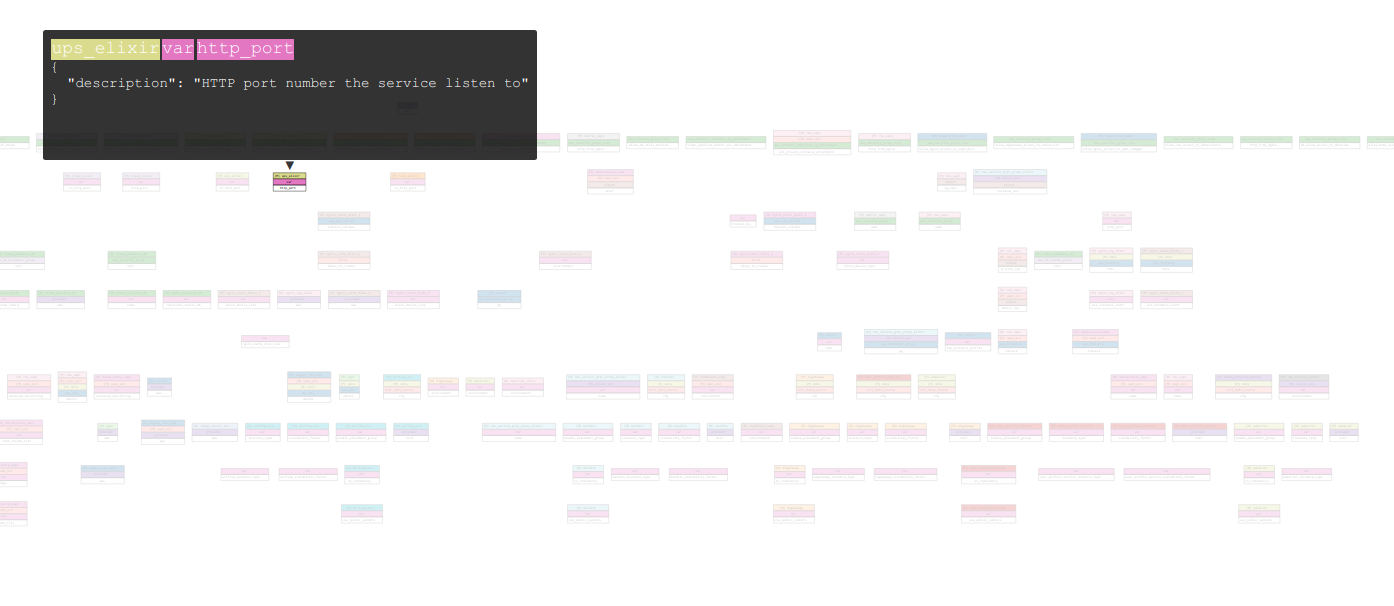

Terraform makes it easy to manage tens of thousands of infrastructure components and even visualize it

Cloud providers like AWS, Azure, etc make it extremely easy to get your product up and running quickly. At Tubi, much like other companies experiencing rapid growth, it became readily apparent to everyone that creating infrastructure resources like EC2 instances, security groups, etc manually via the API or the UI console is inefficient, unmanageable and error prone.

In this post, we will give a brief introduction to Terraform. We will examine how we used Terraform to codify thousands of different AWS resources, including hundreds of EC2 instances running our various services.

Introduction to Terraform

HashiCorp’s Terraform is an open source tool to write, plan and create Infrastructure as Code. Terraform uses a DSL to define infrastructure resources, automatically build a dependency graph and gives you a way to create a plan. It also lets you inspect changes prior to applying them.

Workspaces, State and Components

A basic notion in Terraform is that it maintains its own state. While other tools source of truth comes from inspecting your current resources via the provider’s API, Terraform uses a state file to map its own internal representation of real world resources. To make it easier to maintain multiple states, Terraform provides a container for state file management called Workspace. At Tubi, we use the Workspace feature to manage development, staging and production environments. Throughout this post, we use the terms workspace and environment interchangeably.

As the infrastructure becomes larger and larger, maintaining a single state file, even if split across development, staging and production environments, can become unwieldy and slow. Since terraform state is nothing more than a file, and workspaces are simply sugar around folders containing state files, we can split our large state into multiple different components. For example,. frontend and backend are separated as two components. Now we can combine environment and component, to give us staging frontend, production frontend, staging backend and production backend.

Terraform at Tubi

Armed with the ability to cleanly separate our different environments as well as break down our state into smaller components, we settled on a simple layout for our Terraform code.

.

├── environments

│ ├── default.tfvars

│ ├── production.tfvars

│ └── staging.tfvars

├── components

│ ├── backend

│ ├── common

│ ├── frontend

│ └── global

└── modules

├── ebs-volumes

├── ec2-private-instance-cluster

└── vpc

The global component does not distinguish environments, useful for shared singleton resources like IAM roles and Route53 hosted zones. The common component is useful for defining resources that do have a staging/production environment but are typically shared by all the other components, for example defining the VPC networking layout.

The environments directory contains variable definitions for each, you guessed it, environment. In our case, we want the staging environment to be a mini replica of our production environment. So we use the .tfvar files to define things like number of instances and instance types for each service. For example, production may define 100 beefy machines for ad serving services whereas staging may have 4 small ones.

To standardize running Terraform, we have a simple python wrapper. For example, to create the production frontend infrastructure, Tubi engineers execute

$ infra terraform --environment production frontend

The above command will switch to the production terraform workspace, change directory to frontend component, and execute the Terraform plan stage. Essentially, with some validation steps omitted for brevity, the above command is equal to

$ cd terraform/components/frontend

$ terraform workspace select production

$ terraform plan --var-file=../../environments/production.tfvars --out=plan_file

(optional) $ terraform apply --var-file=../../environments/production.tfvars plan_file

Engineers at Tubi can then take the generated plan from plan_file and open a pull request, which is reviewed like normal code and can then apply their changes once the code is merged into master.

Terraform has made it easy for us to have separate staging and production environments that can be launched by pressing a button. In follow-up posts, we will dive deep into specifics around some of the Terraform modules we built, as well as take a look at how we use Ansible for software provisioning and deployment. If you are excited about infrastructure and automation, we are actively hiring in San Francisco and Beijing, drop us a line.

Thanks to Tim Bell